Columbia Pike and South Arlington have been called home by several African American trailblazers, activists, and organizations that work toward the noble goals of equality and freedom for all. During Black History Month we celebrate the people and places that have contributed to our community’s history and diversity.

PROMINENT PEOPLE

James “Uncle Jim” Parks was born a slave in 1843 on the grounds of Arlington House, the estate of the Custis-Lee family. Parks was 18 at the beginning of the Civil War and witnessed Union soldiers as they fled from the First Battle of Bull Run. The Union army entrenched itself at Arlington House and Parks helped the soldiers build Fort McPherson and Fort Whipple (now Fort Myer) on the grounds. A year later, in 1862, he was freed under the terms of the will left by his former owner, George Washington Parke Custis.

James “Uncle Jim” Parks was born a slave in 1843 on the grounds of Arlington House, the estate of the Custis-Lee family. Parks was 18 at the beginning of the Civil War and witnessed Union soldiers as they fled from the First Battle of Bull Run. The Union army entrenched itself at Arlington House and Parks helped the soldiers build Fort McPherson and Fort Whipple (now Fort Myer) on the grounds. A year later, in 1862, he was freed under the terms of the will left by his former owner, George Washington Parke Custis.

When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton signed the orders designating the Arlington House estate as a military burial ground, Parks joined the Army and worked as a gravedigger and maintenance man digging the very first graves for Arlington National Cemetery.

Respectfully known as “Uncle Jim,” Parks became a vital source of information when, in 1925, Congress decided to restore Arlington House, providing a complete record of the grounds’ layout and the people who inhabited the plantation – the slaves and the Custis-Lee family. Upon his death in 1929, the Secretary of War granted permission for Parks to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The only person buried there who was born on the old plantation, Jim Parks was laid to rest with full military honors: a fitting tribute to a man whose life linked Arlington’s past and present.

Source: National Parks Service

Dr. Charles Richard Drew was a prominent surgeon and pioneer in the field of blood transfusions who became known as the “father of the blood bank.”

Dr. Charles Richard Drew was a prominent surgeon and pioneer in the field of blood transfusions who became known as the “father of the blood bank.”

Drew was born in the District of Columbia in 1904 and moved to Arlington’s Butler-Holmes subdivision, located in what is now the Penrose neighborhood, in 1920. He earned degrees from Amherst College, McGill University, and Columbia University before serving as a faculty member at Howard University School of Medicine and as a surgeon at the affiliated Freedmen’s Hospital in D.C.

He was the first African American to serve as an examiner for the American Board of Surgery and the first to earn a medical doctorate from Columbia. The research and dissertation that earned him that degree led to a revolution in how blood is collected, stored, and transported for medical use.

During World War II, Drew’s groundbreaking technique for processing and storing blood plasma would save thousands of British and American lives. As medical supervisor of the “Blood for Britain” project, he oversaw the collection of some 14,500 pints of plasma, according to some reports.

In 1941, Drew was appointed medical director of the American Red Cross, where he established the first modern blood bank and bloodmobiles, forever earning him the distinction “the father of the blood bank.”

On April 1, 1950, Drew died in a car accident on his way to volunteer at a free clinic in Tuskegee, Alabama. Since then, Drew’s descendants have gone on to become school superintendents, physicians, community activists, marine biologists, local union leaders, firefighters, counselors, Air Force pilots, and teachers.

The Drew House in Arlington, VA was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and serves as a reminder of Dr. Charles Drew’s years of persistent training and work and his extraordinary accomplishments in medicine and civil rights. It is a monument to Drew’s achievements in education and science.

Evelyn Reid Syphax was a native of Lynchburg who graduated from Virginia Union University in 1948 with a bachelor’s degree in English and language arts. She earned a master’s degree at New York University. Moving to Arlington in 1951, she taught third- and fourth-grade classes at a number of Arlington elementary schools and in 1956 married Archie Syphax Sr., Arlington’s first African-American firefighter.

Evelyn Reid Syphax was a native of Lynchburg who graduated from Virginia Union University in 1948 with a bachelor’s degree in English and language arts. She earned a master’s degree at New York University. Moving to Arlington in 1951, she taught third- and fourth-grade classes at a number of Arlington elementary schools and in 1956 married Archie Syphax Sr., Arlington’s first African-American firefighter.

She remained dedicated to education throughout her life, founding the Syphax Child Care Center in 1963 and the Arlington Montessori School in 1966. She joined the Virginia Union University (VUU) board of trustees in 1979 and served on the Arlington School Board from 1980-84, including terms as chairman and vice chairman. In the 1990s, she became the largest donor ever to the university with a bequest of $1 million.

After her death in 2000, the Arlington School Board named an annex near the Arlington Education Center in her honor and in 2010, VUU renamed their school of education the “Evelyn R. Syphax School of Education, Psychology and Interdisciplinary Studies.”

Syphax was a founding member of the Black History Museum of Arlington, originally a virtual “museum without walls,” that established a physical location last May on Columbia Pike.

Sources: Founder’s birthday celebration supports growth of Black Heritage Museum, Inside Nova; University’s School of Education Renamed to Honor AKA Soror Evelyn Syphax, Progressive Geek

Dr. Talmadge T. Williams was a valued and distinguished public citizen of Arlington County for nearly 40 years. He was a visionary community leader and a trusted friend of many. He spent much of his life dedicated to preserving Arlington’s rich cultural history, highlighting those contributions made by the African American community.

He served as president of the Arlington branch of the NAACP, co-chairman of the Arlington Bicentennial Celebration Task Force, and led an initiative called Computers 4 Students, designed to close achievement gaps. He was also active in Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity and served in leadership roles with the Bluemont Civic Association and the Ballston Partnership. He served on boards advising the George Mason University School of Education and the Arlington Chief of Police.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington who dedicated the last 15 years of his life to finding the Museum a permanent, physical location. He was also instrumental in the efforts to have the reconstructed Washington Boulevard Bridge over Columbia Pike renamed “Freedman’s Village Bridge” and initiated the creation of the Freedman’s Village model by architectural students at Howard University.

After his death in September 2014, the Arlington County Board recognized October 18, 2014, as ‘Tribute Day for Dr. Talmadge T. Williams’ in Arlington County “in recognition of his life-long contributions to the people of Arlington County.”

Sources: Effort for Black Heritage Museum to continue after death of visionary, Inside Nova; Tribute Day for Dr. Talmadge T. Williams, Arlington County

PROMINENT PLACES

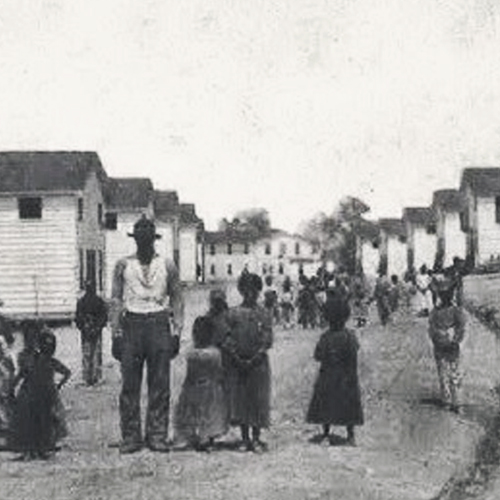

Freedman’s Village was established in 1863 as a camp for newly freed slaves after blacks from Virginia and beyond flooded the District of Columbia following the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Due to overcrowding in the District, the government searched for a location outside of the city for a new encampment. Occupied by the Union army since with start of the Civil War in 1861, Arlington emerged as a sensible choice for the new camp. On May 5, 1863, Lieutenant Colonel Elias M. Greene, chief quartermaster of the Department of Washington, and Danforth B. Nichols of the American Missionary Association officially selected the Arlington Estate as the site for Freedmen’s Village, which they intended to be a model community for freedpersons.

Within a few weeks, 100 former slaves settled on the chosen site, located about one-half mile to the south of the Arlington mansion. The following December, Freedman’s Village was officially dedicated with a ceremony attended by members of Congress and other notables.

The village turned into a semi-permanent settlement and the government developed facilities and infrastructure to support the several thousand residents. In spite of the issues and challenges residents faced, and the eventual closure of the village, living at Freedman’s Village was the first experience of a life out of bondage for thousands of African Americans, including a number of the former Custis slaves. Here, on the grounds of a plantation that had been built and maintained by the labor of enslaved blacks, residents began a new phase in their experience. With legal rights and freedoms, these people could, at least partially, determine their own destinies.

In that sense, the experience of the community’s residents, in finally realizing some of the promises of American freedoms while living at Arlington, was an appropriate precursor to what the Arlington estate would become; a national memorial ground remembering the sacrifices of thousands who defended the very freedoms which the freedmen first experienced on the Arlington grounds.

Source: National Parks Service

Harry Gray House was built by former slave Harry W. Gray. It is a rare example of the brick rowhouse in the Italianate style and is the only surviving building of its type in Arlington. The Gray House represents the monumental shift from slavery to middle-class citizenship for African Americans in the decades following the Civil War.

Harry Gray House was built by former slave Harry W. Gray. It is a rare example of the brick rowhouse in the Italianate style and is the only surviving building of its type in Arlington. The Gray House represents the monumental shift from slavery to middle-class citizenship for African Americans in the decades following the Civil War.

Gray was born into slavery around 1851 at General Robert E. Lee’s Arlington House estate as the sixth child of Thornton and Selina Noms Gray. His mother, Selina Gray, was Mary Custis Lee’s trusted household slave and personal assistant for nearly 30 years. Harry Gray was documented to have been a mason’s assistant on the property.

Following the Civil War, Gray and his family established themselves at the government-sponsored Freedman’s Village while assimilating into their newfound societal roles. In 1880, Gray and his wife, Martha (Hoard) Gray, a freed slave from James Madison’s Montpelier plantation, purchased a nine-acre tract in nearby Johnson’s Hill and it was here a year later that Gray finished building his house. The property remained in the Gray family until 1979, nearly 100 years after it was built.

The home, located at 1005 S Quinn St, was designated a historical site in 2003 to honor the impressive work of this “amateur builder.”

Source: Arlington Projects & Planning

Mount Zion Baptist Church is the oldest of the Black congregations in Arlington. The church traces its roots back to The Old Bell Church established in Freedman’s Village. In 1866, when the closing of Freedman’s Village was drawing near, the congregants moved to Alexandria County, now Arlington County, and named their new church Mount Zion Baptist Church.

Mount Zion Baptist Church is the oldest of the Black congregations in Arlington. The church traces its roots back to The Old Bell Church established in Freedman’s Village. In 1866, when the closing of Freedman’s Village was drawing near, the congregants moved to Alexandria County, now Arlington County, and named their new church Mount Zion Baptist Church.

In 1930, a new church was erected at the Arlington Ridge Road site. In 1942, the federal government condemned the property to make way for a network of roads. The Odd Fellows Hall at Columbia Pike and South Ode Street was selected as a temporary place of worship.

In 1944, the current property on 19th St was purchased. Groundbreaking services were held on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1944, and the first services were held in the new building on the first Sunday in July 1945.

Today it is a magnificent temple, a light shining in the darkness, “A city set on a hill” reaching out to the masses in an attempt to fulfill the works of the Master, “To heal the sick, feed the poor, clothe the naked, comfort the sorrowful and bring deliverance to the captives.”

Sources: Mt. Zion Baptist Church; The Historical Marker Database